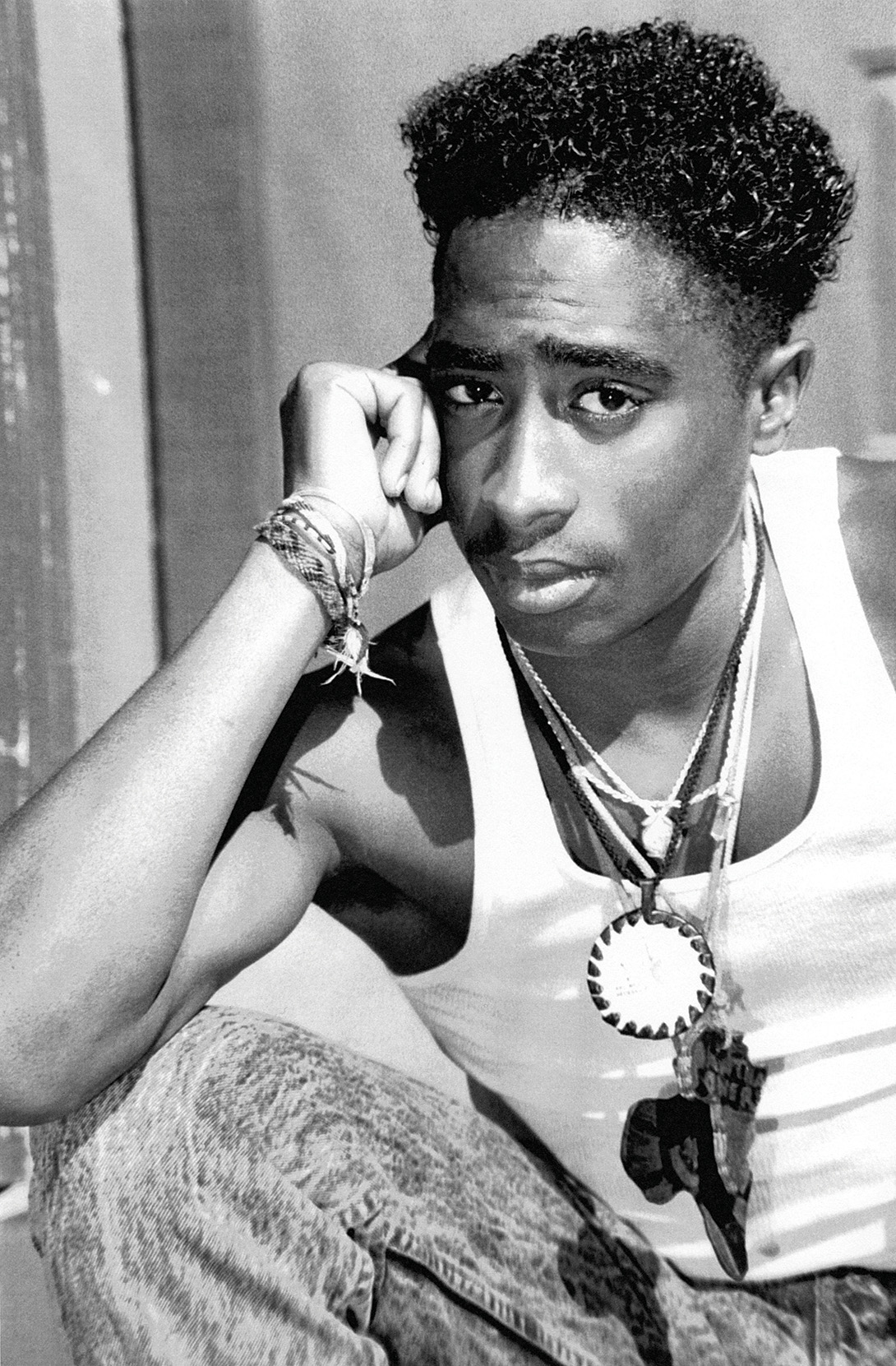

Today, when we think of a modern revolutionary, we think of the famous rapper, Tupac. Tupac’s mother, Afeni Shakur was revolutionary in her own right, but did you know that Tupac was named after an Incan revolutionary? His name was Túpac Amaru II. He would be one of the first influencers of freedom from the Spanish colonial system. He inspired future revolutionaries like Simon Bolivar and Che Guevara.

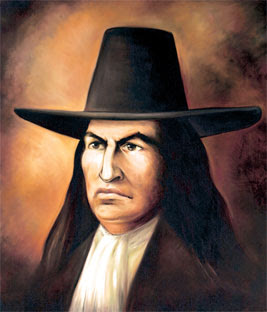

The last emperor of the Incan Empire himself was named Túpac Amaru I. Tupac roughly translates as “royal” or “shining” also spelled Thupaq in the Incan language of Quechua. Amaru means “serpent”. The Royal Serpent. A fun fact is that the Incan Empire was referred to by the natives as Tawantinsuyu, meaning the four regions. The four regions all connected at the capital, Cusco (remember the Emperor’s New Groove Disney movie 👀). The actual word of Inca or Inka means “ruler” or “lord” which referred to the ruling class/family of the empire. Like most colonizing countries, they incorrectly named the empire because simply, they didnt care much for the details, just for the profit they could make. In 1572, 40 years after Pizarro declared conquest on the Incan Empire, Túpac Amaru I was captured by the Spanish and executed, leading to the official end of the original empire.

Nearly 200 years later, the Spanish renamed majority of the empire, Peru. The Spanish colonial system introduced a hierachial class system, with the Incans (the natives) at the bottom of the class order. José Gabriel Condorcanqui Noguera was born in a province of Cusco, to Miguel Condorcanqui Usquionsa Túpac Amaru and María Rosa Noguera. His father was a provincial magistrate better known as a kuraka of three towns in the Tinta district. Túpac’s parents died when he was twelve years old, and he was raised by an aunt and uncle. He was recognized as an elite Quechua (Incan) and was educated at a school in Cusco for sons of indigenous leaders. He spoke Quechua and Spanish, and learned some Latin from the Jesuits at school. At the age of 21, he married Micaela Bastidas Puyucahua of Afro-Peruvian and indigenous descent. Shortly after his marriage, he succeeded his father as kuraka, giving him rights to land. He became the head of several Quechua communities and a regional merchant and muleteer, inheriting 350 mules from his father’s estate. His regional trading gave him contacts in many other indigenous communities and access to information about economic conditions. He also inherited the chiefdom of Tungasuca and Pampamarca from his older brother, governing on behalf of the Spanish governor. He was upwardly socially mobile, and in Cusco he had connections with distinguished Spanish and Spanish American (creole) residents. “The upper classes in Lima saw him as a well-educated Indian,” whatever European ancestry he might have had. I guess they had that one drop blood that we know about in the States.

In 1720, the Spanish had abolished the encomienda system which gave conquerers the right to take the conqueredor native people as their laborers or slaves, yet most natives of the region were pushed into forced labor. Most natives worked under the supervision of a master. The little wage that was acquired by workers was heavily taxed and continued their indebtedness to Spanish masters. The church also had a hand in extorting natives through collections for saints, masses for the dead, domestic and parochial work on certain days, forced gifts, etc. Those not employed in forced labor were still subject to the Spanish provincial governors, or corregidores who also heavily taxed any free natives, similarly ensuring their financial instability.

Túpac’s interest in the Incan cause had been spurred by the re-reading the outlawed book, The Royal Commentaries of the Incas, a book about the history and culture of the ancient Incas. It was outlawed by the Spanish for fear of an Incan uprising. At the same time Spain released the Bourbon Reforms which positioned Cusco to lose financial benefits of nearby Silver Mines. In 1778, Spain raised sales taxes on goods and alcoholic beverages while tightening the rest of its tax system in its colonies in part to fund its participation of the American Revolutionary War. Túpac’s native pride coupled with his hate for the Spanish colonial system, caused him to sympathize and frequently petition for the improvement of native labor rights; even using his wealth to help alleviate the taxes and burdens of the natives. After many of his requests fell on deaf ears and the economic hardships of the area continued, Túpac decided to organize a rebellion. Túpac was motivated in part by the reading of a popular Incan prophecy called the Inkarri which stated that the Incan would rise again. Not to mention the recent success of the American Revolution where colonists were able to gain freedom from England. He officially changed his name to Túpac Amaru II, claiming he was descended from the last Incan ruler.

On November 4th, 1780, Túpac and his co-conpirators took captive governor Antonio de Arriaga, forcing him to correspond with the powers that be for money and arms. Six days later, Túpac allowed Arriaga’s slave to execute him in front of the masses. The first attempt to hang Arriaga failed when the noose snapped but he was successfully executed on the second attempt. From there Túpac began moving through the countryside, releasing his first proclamation announcing, “that there have been repeated outcries directed to me by the indigenous peoples of this and surrounding provinces, outcries against the abuses committed by European-born crown officials… Justified outcries that have produced no remedy from the royal courts” to all the inhabitants of the Spanish provinces. He went on in the same proclamation to state, “I have acted … only against the mentioned abuses and to preserve the peace and well-being of Indians, mestizos, mambos, as well as native-born whites and blacks. I must now prepare for the consequences of these actions.” He went on to quickly assemble an army of 6,000 natives who had abandoned their work to join the revolt. The rebels looted the Spaniards’ houses and killed their occupants. His supporters were Incan, mixed race, and creoles (spanish landowners). Incan communities often sided with the rebels( Túpac’s army), and local militias put up little resistance. It was not long before Túpac’s forces had taken control of almost the entire southern Peruvian plateau.

Túpacs wife, Micaela Bastidas, commanded a battalion of insurgents and was responsible for the uprising in the San Felipe de Tungasuca region. She is also often credited to being more daring and a superior strategist, compared to her husband. By December 1780 Túpac began to lead an uprising of indigenous people but the Spanish military proved to be too strong for his army of 40,000–60,000 followers. After being repelled from Cusco, Túpacs army went around the country gathering forces to attempt to fight back. As time went on the upper-caste creoles started to abandon him to rejoin the loyalist forces. Further defeats and Spanish offers of amnesty for rebel defectors hastened the collapse of Túpac’s forces.

By the end of February 1781, Spanish authorities began to gain the upper hand. A mostly indigenous loyalist army of up to between 15,000 and 17,000 troops led by Jose del Valle had the smaller rebel army surrounded by March 23. By April 5th, Túpac and his family were betrayed and captured the next day along with battalion leader Tomasa Tito Condemayta, who was the only indigenous noble who would be executed alongside Túpac. Túpac was forced to watch the deaths of his wife Micaela Bastidas, his eldest son Hipólito, his uncle Francisco Tupa Amaro, his brother-in-law Antonio Bastidas, and some of his captains before his own death which he himself was quartered. The four horses running in opposite directions failed to tear his limbs apart resulting in Túpac being beheaded. He was beheaded on the main plaza in Cuzco, in the same place his apparent great-great-great-grandfather Túpac Amaru I had been beheaded.

Túpac Amaru’s capture and execution did not end the rebellion. In his place, his surviving relatives continued the war. The war was also continued by Túpac female commander named Bartola Sisa. Sisa led a resistance of 2,000 troops for several months until they were eventually brought down by the Spanish army. Government efforts to destroy the rebellion were frustrated by, among other things, a high desertion rate, hostile locals, scorched-earth tactics, the onset of winter, and the region’s altitude (most of the troops were from the lowlands and had trouble adjusting). A preliminary treaty and prisoner exchange were conducted on December 12, and Túpac’s forces formally surrendered on January 26, 1782. The last organized remnants of the rebellion would be vanquished by May 1782, though sporadic violence continued for many months. Many of the leaders who fought in the rebellion after Túpac Amaru’s death were discovered to be women (32 out of the 73) and were later acknowledged by the eventual liberator of Spanish America, Simón Bolívar in his speech in 1820.

The ultimate death toll was estimated at 100,000 Indians and 10,000–40,000 non-Indians. Following the execution of Túpac, laws were passed to ban the Quechua language, the wearing of indigenous clothing, and virtually any mention or commemoration of Inca culture and history. However colonial authorities lacked the resources to enforce these laws and they were soon largely forgotten.

Túpac Amaru was a true revolutionary. Like the many revolutionaries of the New World, Túpac Amaru was one of the first to take up his sword and lead his people to freedom, like so many after. Similar to many stories of rebellion in the New World, their purpose was to inspire future generations to fight back and finally free themselves from the oppresive colonial system. The same can be applied today.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Túpac_Amaru_II

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Túpac_Amaru