During a time when African Americans found it almost impossible to own land, let alone a house in the 19th century, a community in New York became a safe haven for many to call home. A community where African Americans for once could live as free citizens. That was until it was decided that their community was targeted for future green space, which became known as Central Park in New York City.

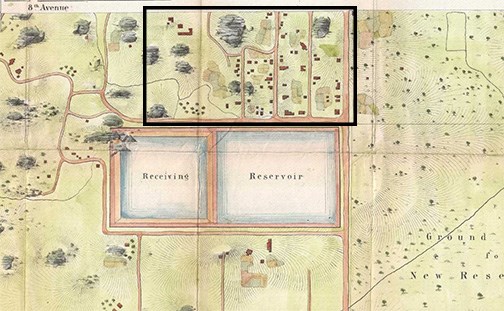

In 1824, a white farmer named John Whitehead purchased land which was outside of what was considered the core of New York City, a much smaller version than modern-day. One year later Whitehead, started to sell parts of his land, three lots being sold to a young African American man named Andrew Williams for $125. On the same day, the American Methodist Episcopal Zion Church trustee, Epiphany Davis bought twelve lots for $578. The AME Zion Church bought six additional lots the same week, and by 1832, at least 24 lots had been sold to African Americans. The land would be called Seneca Village. Five acres of a nearby development called “York Hill” was sold to William Matthews a young African American who had purchased land in Seneca Village as well. By 1827, New York officially outlawed slavery and a nearby reservoir in York Hill was being built which caused an influx of several freed African Americans to nearby Seneca Village.

There are several theories surrounding the origin of the name of Seneca Village, the most popular being – a roman philosopher who wrote books that were read by several abolitionists and activists, named after the Seneca Nation of Native Americans, named after Senegal where most could trace their origins to in Africa, and a possible code name that was given by the Underground Railroad as it was a location that many slaves escaped to.

Later, during the potato famine in Ireland, which resulted in the Irish migration to the United States, many Irish immigrants came to live in Seneca Village, swelling the village’s population by 30 percent. Both African Americans and Irish immigrants were marginalized and faced discrimination throughout New York City. Despite their social and racial conflicts elsewhere, the African Americans and Irish in Seneca Village lived close to each other. By 1855, one-third of the village’s population was Irish. George Washington Plunkitt, who later became a Tammany Hall politician, was born in 1842 to two of the first Irish settlers in the village, Pat and Sara Plunkitt.

In 1855, Seneca Village had 264 residents. After slavery was abolished in New York, African American men in the state could vote as long as they had $250 worth of property and had lived in the state for at least three years. Of the 13,000 African American New Yorkers, 91 were qualified to vote, ten lived in Seneca Village. The purchase of land by African Americans had a significant effect on their political engagement. African Americans in Seneca Village were extremely politically engaged in proportion to the rest of New York.

The village had three churches, two schools, and two cemeteries. The AME Zion Church, a denomination officially established in lower Manhattan in 1821, owned a church building and property for burials in Seneca Village beginning in 1827. The African Union Church purchased lots in Seneca Village in 1837. The church building (in the basement) contained one of the city’s few black schools at the time, Colored School 3, founded in the mid-1840s. Seneca Village also existed as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

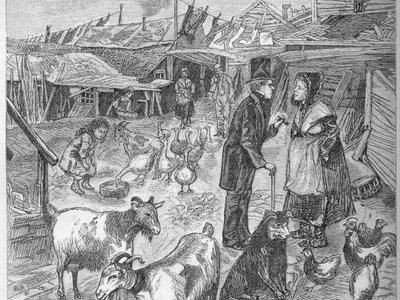

The one-story frame-and-board houses in Seneca Village were referred to as “shanties”, which to the rich showcased the poor appearance of the area. To most, the shanties were an improvement to the cramped tenements of Lower Manhattan. Land ownership among black residents in Seneca Village was much higher than that in the city as a whole: more than half of blacks owned property in 1850, five times as much as the property ownership rate of all New York City residents. One-fifth of Seneca Village’s inhabitants owned their residences. Many of Seneca Village’s black residents were landowners and relatively economically secure compared to their downtown counterparts.

However, many residents of Seneca Village were poor since they worked in service industries such as construction, day labor, or food service, and only three residents (two grocers and an innkeeper) could be considered middle-class. Many black women worked as domestic servants. Many residents “squatted”, boarding in homes they did not own. Many relied on the abundant natural resources nearby, such as fish from the nearby East River and Hudson River, and the firewood from surrounding forests. Some residents also had gardens and barns and fed their livestock scraps of garbage.

To some New York white citizens like Mordecai Noah, the founder of The New York Enquirer, who was especially well-known for his attacks on African Americans, said “the free negroes of this city are a nuisance incomparably greater than a million slaves.” The Seneca Village community was referred to using racial slurs. Park advocates and the media began to describe Seneca Village and other communities in this area as “shantytowns” and the residents there as “squatters” and “vagabonds and scoundrels”; the Irish and black residents were often described as “wretched” and “debased”. The residents of Seneca Village were also accused of stealing food and operating illegal bars. The tip of the island of Manhattan was overflowing with people. The slums were spilling over as more and more immigrants arrived. None of these conditions appealed to well-off New Yorkers, who had already started migrating further uptown, or out of town, by the 1840s.

Members of the city’s elite were publicly calling for the construction of a new large park in Manhattan to block the further encroachment of immigrants and freed African Americans who “lessened the value of their prominent city”. The real reason. The other reason was to compete with its long time rival, Great Britain who was known for its city parks at the time. In 1845, the editor of the New York Evening Post praised Britain’s acres of parks, noting: “These parks have been called the lungs of London.” The pro-park lobby was largely “affluent merchants, bankers, and landowners”, who wanted a “fashionable and safe public place where they and their families could mingle and promenade”. Two of the primary proponents for the city park were William Cullen Bryant, the editor of the New York Evening Post, and Andrew Jackson Downing, one of the first American landscape designers. The first site of land that was scouted for the new park was Jones’s Wood, a 160-acre tract of land between 66th and 75th Streets on the Upper East Side. It hosted wealthy families who objected to the city taking their lands and were able to obtain an injunction to block the acquisition, and the transaction was invalidated as unconstitutional. The second site proposed was a 750-acre area labeled “Central Park”, bounded by 59th and 106th Streets between Fifth and Eighth Avenues which included Seneca Village on the West side. The New York State Legislature passed the Central Park Act in July 1853; the act authorized a board of five commissioners to start purchasing land for a park, and it created a Central Park Fund to raise money. Egbert Ludovicus Viele, the park’s first engineer, wrote a report about the “refuge of five thousand squatters” living on the future site of Central Park, criticizing the residents as people with “very little knowledge of the English language, and with very little respect for the law”.

In 1853, the Central Park commissioners concluded their tax assessment report for the land that would be taken over to create Central Park. Residents were offered an average of $700 for their property. The minority of Seneca Village residents who owned land were compensated. For instance, Andrew Williams was paid $2,335 for his house and three lots, and even though he had originally asked for $3,500, the final compensation still represented a significant increase over the $125 that he had paid for the property in 1825. Epiphany Davis was not as fortunate, losing hundreds of dollars.

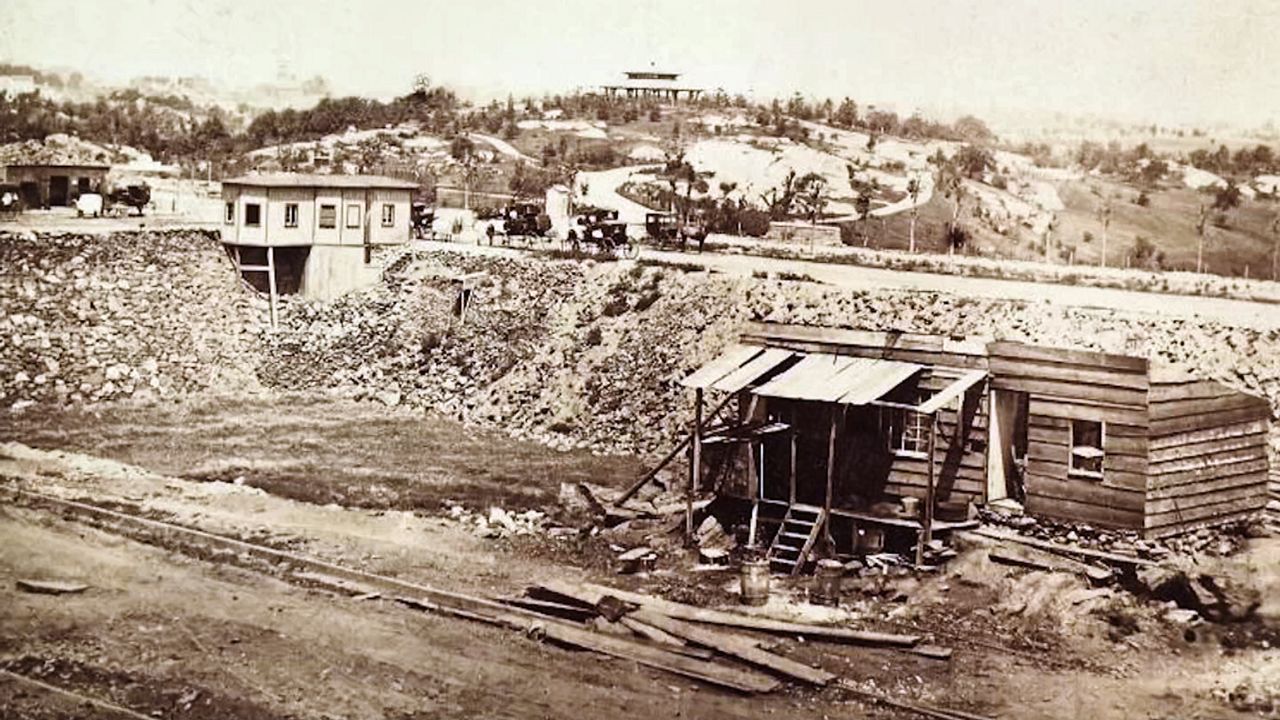

Clearing for the park occurred as soon as the Central Park commission’s tax assessment report was released. The city began enforcing little-known regulations and forcing Seneca Village residents to pay rent. Members of the community fought for two years to retain their land. However, in mid-1856, Mayor Fernando Wood prevailed, and residents of Seneca Village were given final notices. In 1857, the city government acquired all private property within Seneca Village through eminent domain, and on October 1, city officials in New York reported that the last holdouts living on land that was to become Central Park had been removed. A newspaper account at the time suggested that Seneca Village would “not be forgotten … [as] many a brilliant and stirring fight was had during the campaign. But the supremacy of the law was upheld by the policeman’s bludgeons” – what a nice thought 😒.

All of the inhabitants of the village were evicted by 1857, and all of the properties within Central Park were razed. Elsewhere in Central Park, the impact of eviction was less intense. Squatters and hog farmers (mostly immigrants from Ireland and Germany) were the most affected by Central Park’s construction, as they were never compensated for their evictions.

Years later in 1871, The New York Herald reported that two coffins were discovered, one “enclosing the body of a Negro, decomposed beyond recognition.” A half-century later, a gardener named Gilhooley inadvertently found a graveyard from Seneca Village while turning the soil at the same site. The site was named “Gilhooley’s Burial Plot” in honor of his discovery. For centuries, the legend of Seneca Village was forgotten until 1992 when Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar’s 1992 book The Park and the People: A History of Central Park, described the community extensively.

The Seneca Village Project was formed in 1998. It is dedicated to raising awareness about Seneca Village’s significance as a free, middle-class black community in 19th-century New York City. In February 2001, a plaque was placed in the park commemorating the site where Seneca Village once stood. In 2019, the city announced a request for proposals for a statue honoring the Lyons family, property owners Seneca village. The statue would be placed at 106th Street in the North Woods section of the park.

Archeological digs took place in 2004, 2005, and 2011. The excavations uncovered the foundation walls and cellar deposits of the home of William Godfrey Wilson, a sexton for All Angels’ Church, and a deposit of items in the backyard of two other Seneca Village residents. Archaeologists filled over 250 bags with artifacts, including the bone handle of a toothbrush and the leather sole of a child’s shoe.

At the end of the paragraph of the Central Park plaque, there’s a telling line which sums up what makes this story such a tragedy “The residents and institutions of Seneca village did not re-establish their long-standing community in another location”. It was an African American community that allowed many to finally have a place to call home and with the razing of their land, their community was never the same again. This is a testament to the African American plight in the United States. Once a community, but never the same due to interruption.

Maybe Harlem became the new Seneca, but how could it be, if African Americans didn’t own their land in Harlem, just rent – and more than likely couldn’t vote? Was Harlem even integrated? What if Seneca was never razed. Would this have helped foster the relations between African Americans, Irish, and Germans? Would they have been able to come together to challenge those who oppressed them – the white elite? Or am I dreaming because… labor unions would eventually be created to separate the African American from the immigrant in the coming years? And why even dream because eventually those same Irish and German immigrants would assimilate into the white elite, further uplifting the white elite agenda?

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seneca_Village

https://timeline.com/black-village-destroyed-central-park-6356723113fa

What a system. Always taking advantage of the weak and downtrodden. Black people must realize that the only strength is money in this world and that unity is strength. Why can’t black learn from the other races? Everyone comes to America most of the time, hand to mouth but they band together. It’s time to start black associations in USA where blacks can go to get help and not depend so much on the Government. The Lord helps those who help themselves. I hope black mothers would teach their black sons how to be responsible towards women and their children. All black men should take Michele Obama’s father as an example. What a man. Why can’t these black cinematic executives produce uplifting films portraying men like that. Can’t they see the response of “Black Panther”? Please wake up black people.

LikeLiked by 1 person