“All For One! and One For All!” – the famous one-liner from the french author, Alexandre Dumas’s widely known book, The Three Muskateers. . Many of us know about his works but little of us know about his family history. As I researched about Alexandre Dumas I learned that not only was he an famous figure, so too was his father. The great Thomas-Alexandre Dumas was a famous general in the French Revolution. One of Napoleon Bonaparte’s most trusted generals. He along with Toussaint Louverture and Abram Petrovich Gannibal was one of the highest-ranking men of African descent to lead a European army.

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas was born Thomas-Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie in Jérémie, Saint Dominique (later known as Haiti). His father was Alexandre Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie who was one of three sons of a French aristocrat family. Alexandre Antoine had followed his younger brother Charles from France to Saint Dominque where he would help his brother work his sugar plantation. After a disagreement, Alexandre Antoine left his brother’s plantation with three of his slaves.

He would then purchase a slave named Marie-Cessette Dumas and have her as his concubine. Their first child was Thomas-Alexandre Dumas. Thomas would spend about 10 years in Saint Dominique on the land of his father’s coffee and cacao plantation with his mother. Until that is, his father decided to return to France and sold Thomas’s mother and other three children (all daughters) to a baron. His father would bring son with him to France. To do this, Alexandre Antoine “sold” his son to a captain which provided free passage to Thomas and the money (as a loan) for his father’s passage to France. Once Thomas set foot in France after arriving in La Havre, France with the captain, his father bought his son back from the captain and freed him.

Thomas would grow up with his father in France living quite a comfortable highly educated life. Thomas would then enlist in the Army as a private. Unlike his noble peers who were able to join the army as commissioned officers due to a rule which enabled men who could show four generations of nobility on their father’s side to qualify to be commissioned as officers, due to race laws in France, he was unable to gain a higher enlistment position. And because he wouldn’t be able to enter as an officer, his father convinced him to create a pseudo name, therefore he would officially enlist as Alexandre Dumas, surprisingly thirteen days after his father passed away.

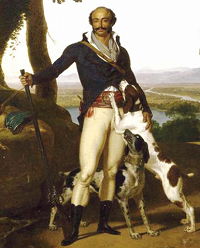

Thomas enlisted in the 6th Regiment of the Queen’s Dragoons. He was described as “6 feet tall, with frizzy black hair and eyebrows… oval face, and brown-skinned, smallmouth, thick lips”. He was “one of the handsomest men you could ever meet. His frizzy hair recalls the curls of the Greeks and Romans.” His face was described as ‘”something closer to ebony than to bronze”.

During the beginning of the French Revolution, his unit was sent to protect the small town of Villers-Cotterêts where he met his future wife Marie-Louise Labouret who was the local innkeeper and national guard leader’s daughter. Thomas was then sent to Paris with his unit to protect citizens during the Champ de Mars Massacre in which he claimed to save around 2,000 people in the massacre. From there he took part in the french’s first attack on the Austrian Netherlands. Thomas was able to capture 12 enemy soldiers while leading a scouting partying of four to eight horsemen.

Thomas went up in rank as Lieutenant- colonel (second in command) of the Black Legion which consisted of all freed black men fighting for France. Once that legion was disbanded due to its main lieutenant (Thomas’s old teacher of swordsmanship) being found of misusing government funds, Thomas was promoted to the rank of Brigadier general. One month later he was promoted again to the General of Division and later became the Commander in Chief of the Western Pyrenees. He would become the commander in chief of the Army of the Alps and the Army of the West. Henri Bourgeois (a famous french historian) would characterize Thomas as “fearless and irreproachable”; a leader who “deserves to pass into posterity and makes a favorable contrast with the executioners, his contemporaries, whom public indignation will always nail to the pillory of History!”

Thomas was one of the generals assigned to the Army of the Rhine and then assigned to the Army of Italy, under the famous General Napoleon Bonaparte. Because it seems that Thomas had some morals about himself and didn’t agree with some of Napoleon’s colonial-like ways, the tension between Thomas and Bonaparte was common. Thomas resisted Napoleon’s policy of allowing French troops indiscriminately to claim Austrian property for their own. A normal side effect of colonization. In December 1796, Dumas was put in charge of a division besieging Austrian troops at the city of Mantua and prevented Austrian reinforcements to enter the city. By February, the city was overtaken by the French.

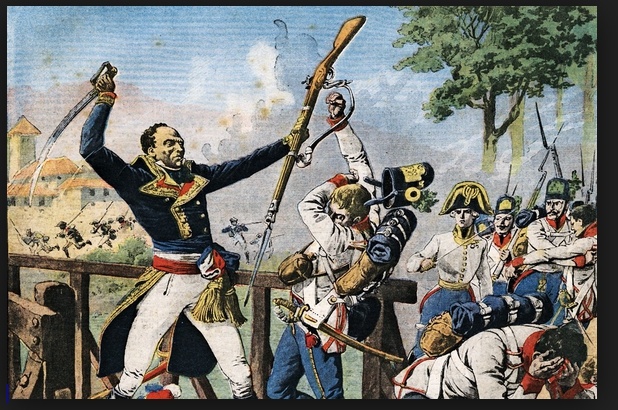

Unfortunately, communication with Napoleon minimized Thomas’s involvement in the overtaking of Mantua. Thomas found out and wrote a letter directly to Napoleon explaining what happened and that the aide de camp that reported the battle did so incorrectly. Because he spoke up, Thomas was removed completely from the battle that was reported to the governing body at the time. In addition to being omitted, Thomas was also lowered in rank, despite petitions from his soldiers attesting to his valor. Thomas continued in his lower rank and was nicknamed der Schwarze Teufel (“Black Devil”, or Diable Noir in French) by opposing Austrian troops. Thomas went on to be called “the Horatius Cocles of the Tyrol” (after a hero who had saved ancient Rome), and won back favor with Napoleon and was rewarded with a new role as cavalry commander of all French troops in the Tyrol (area in North Italy) and received a pair of pistols from Napoleon. Dumas was also placed as a military governor in the province of Treviso, Italy.

Thomas was then ordered to a secret campaign where he only learned of the purpose of the mission, to conquer Egypt while aboard the Guillaume Tell, in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea. He had been appointed as commander of all cavalry in the Army of the Orient (1798). Shortly after the French landed in the Egyptian port of Alexandria, the city was conquered. After fighting, Napoleon sent Dumas to pay ransom to some Bedouins who had kidnapped French soldiers. The expedition’s chief medical officer recounted in a memoir that local Egyptians, judging Dumas’s height and build versus Napoleon’s, believed Dumas to be in command. Seeing “him ride his horse over the trenches, going to ransom the prisoners, all of them believed that he was the leader of the Expedition.” As the army marched to Cairo, many soldiers fell ill or died due to poor conditions and an unforgiving desert climate. Thomas and other generals vented criticisms of Napoleon’s leadership. Napoleon later found out and confronted Thomas about it. In his memoirs, Napoleon remembered threatening to shoot Thomas for sedition. Thomas requested leave to return to France, and Napoleon did not oppose it. Napoleon was reported to have said: “I can easily replace him with a brigadier.”

Thomas returned to Egypt, where he found a cache of gold and jewels stored beneath a house in Cairo. He gave his findings to Napoleon, the colonizer. Thomas was instrumental in putting down an anti-French revolt in Cairo by charging into the Al-Azhar Mosque on horseback. Afterward, Napoleon told him: “I shall have a painting made of the taking of the Grand Mosque. Dumas, you have already posed as the central figure.” Unfortunately, the painting that was commissioned eleven years later, shows a white man charging into the mosque. On his return to France, Thomas’s ship was capsized and he and the crew survived but landed in Naples which was at the time overtaken by an opposing army which took him as a prisoner.

Thomas was malnourished and kept out of communication for two years. . During these years, Thomas’s wife lobbied for government assistance to free Thomas to no avail. By the time of his release (because the French army had driven out the opposing army), he was partially paralyzed, almost blind in one eye, had been deaf in one ear but recovered; his physique was broken. He believed his illnesses were caused by poisoning. During his imprisonment, he was aided by a secret local pro-French group, which brought him medicine and a book of remedies.

After returning to France after his release in 1801, he had his son, Alexandre Dumas, with his wife Marie-Louise. He struggled to support his family and repeatedly wrote to Napoleon Bonaparte, seeking back-pay for his time lost while imprisoned and in the military. He died of stomach cancer in 1806. At his death, his son Alexandre was three years old. The boy, his sister, and his widowed mother were plunged into deeper poverty. Marie-Louise worked in a tobacconist’s shop to make ends meet. For lack of funds, the young Alexandre Dumas was unable to get even a basic secondary education. Marie-Louise persistently lobbied the French government to be paid her military widow’s pension. Marie-Louise and the young Alexandre blamed Napoleon Bonaparte’s “implacable hatred” for their poverty.

Fortunately, Thomas Dumas’s legacy was not lost. The life of Thomas – Alexandre Dumas inspired most of his son Alexandre Dumas’s most famous characters. It is because of Thomas Dumas’s life, we have timeless works like The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo. In addition to his son’s accomplishments, his name is also inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, France. In 1913, a statue in his honor was erected in Place Malesherbes in Paris. It stood in Place Malesherbes for thirty years, alongside statues of his descendants, his son Alexandre Dumas, père (erected in 1883), and his grandson, Alexandre Dumas, fils(erected in 1906. The Nazis destroyed the statues during World War II, and since then have never been restored. In 2009, a sculpture in his “honor” was erected in Paris, which just shows broken (slave) shackles. Many believed this was not appropriate because the general had never been a slave.

However, his father did sell and re-purchase him as a slave when he brought Thomas to France, which to most disproves this claim but I agree with critics, he was never a slave, it was something that had to be done for Thomas’s father to bring him to France legally. Tom Reiss, a Thomas Dumas biographer has suggested that the monument is inappropriate for other reasons: “In the race politics of twenty-first-century France, the statue of General Dumas had morphed into a symbolic monument to all the victims of French colonial slavery … There is still no monument in France commemorating the life of General Alexandre Dumas.” A petition created in 2009, is still ongoing which requests the French government to award General Dumas the Légion d’honneur, the highest merit given for military and civic achievements.

The great Thomas Alexandre Dumas was a legendary general who it seems never really did get his right shine, simply because of his race. If he didn’t have one drop of African blood, maybe he would be all in our history books today and there would be no question to his legacy. Unfortunately, this is the way the world works, but at least we know that in addition to the American Revolution, the French revolution was successful with the help of other races not just one, like the history books would like to prescribe. His legacy never died because in addition to his successes as a general, he was successful in producing a successful line of descendants, better known as the Dumas Dynasty.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas-Alexandre_Dumas#cite_note-69

I enjoyed reading this version of the General’s life. Amazing strength. Beautifully written. Thanks

LikeLiked by 2 people

I love this website

LikeLike